As a result of the current extremely challenging consumer environment, there has been an inescapably huge impact on shopping behavior for a variety of reasons, both good and ill. Whether people have been stockpiling “essentials”, shopping for others less able to, ordering online as a default, visiting physical stores less often or buying products and brands purely based on availability rather than choice; everyone has been affected in some way.

But the inevitable $64 million (and a lot more!) question is: “Will this period have a lasting effect on what we continue to put in our trolleys, either physically or virtually?”

The answer depends on many factors but mainly on the length of the global recession we seen certain to tip into, which will affect jobs, salaries and disposable incomes all over the world. If the downturn is indeed protracted, then one trend we can be certain will continue is the move away from “traditional” brands toward cheaper “equivalent” versions. What was already much more than an inconvenience for category incumbents may yet prove to be the tip of the iceberg. The return of choice might well provide an even greater acceleration.

Whatever you call them – private label, own label or own brand – such products have been a mainstay of the UK grocery scene for more than a quarter of a century, and almost all UK households purchase private label (PL) products of some kind. But the influence of PL on the UK grocery landscape is now deepening.

Since 2015, sales of PL products within fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) categories have grown 14.3 percent in value, and 15.8 percent in volume, far outstripping the performance of branded products, which have grown just 3.5 percent in volume and have actually declined 3.7 percent in value terms*.

The sharp growth of PL reflects both retailer push and consumer pull. Economic austerity has affected household budgets and consumer attitudes to spending and, at the same time, discount grocers ALDI and Lidl have expanded, and together account for 68 percent of PL value growth since 2015*. This has happened alongside growing investment in PL by the UK’s “Big Four” UK supermarkets (Tesco, Sainsbury’s, ASDA and Morrisons).

The average UK household now buys a PL product 187 times per year, a 6 percent increase on 2015, meaning that for most households, between 40 and 70 percent of all the groceries they buy are PL**.

The real deal

As consumers have added more and more PL products to their trolleys, supermarkets have not only built sales, they have built powerful new brands. Consumers are beginning to view what were once “just own brand” ranges, selected purely on price, as genuinely desirable brands. As a result, PL growth is outpacing brands in four out of 10 categories where brands hold the dominant share**.

The “Exclusively at Tesco” range, launched in early 2018, is a good example of an evolved “brand led” PL range. To shoppers, these products look and feel like genuine brands, and are marketed as such, though at a lower price point than the competing brand equivalents. The range is now worth £545 million, is purchased by 62 percent of all UK households, and features in one in five Tesco baskets*.

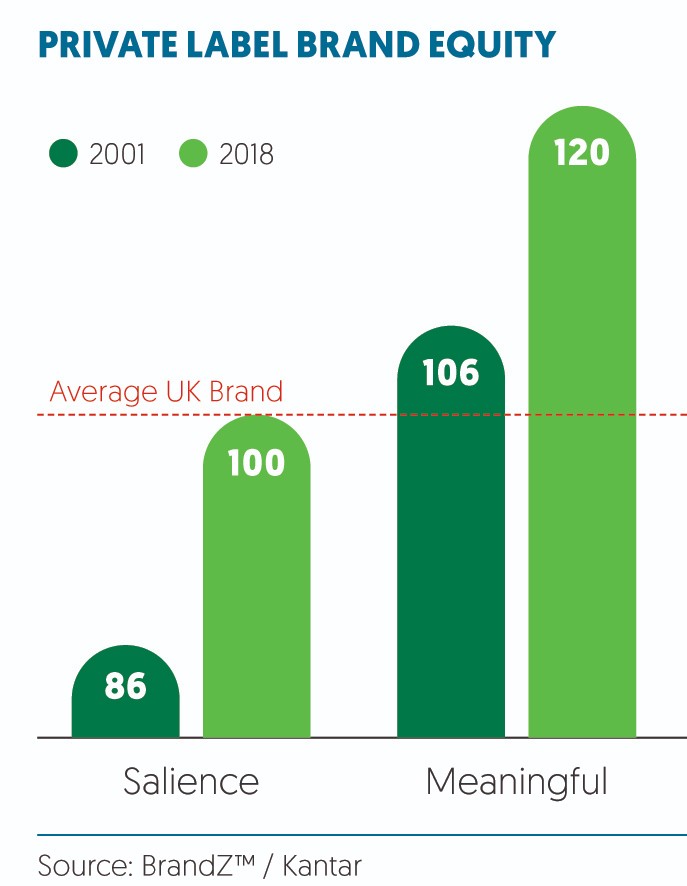

Analysis of the BrandZ™ database from 2011-2018, across seven FMCG categories from water and oral care to detergents and male grooming, further highlights the success of the PL branding revolution and the resultant change in attitude among UK consumers.

Firstly, typical PL Brand Power, a measure of the volume a brand commands based on brand equity, has grown so much in the past decade that it now indexes higher than what we might call “real” brands.

PL ranges still generally lack perceived difference in the minds of consumers (scoring just 49 versus an average of 100); yet the drivers of the overall increase in their brand equity are twofold. PL brands are now better known to shoppers and spring to mind when they shop (we call this “salience”), and they increasingly meet consumers’ evolving needs and make an emotional connection (they are “meaningful”).

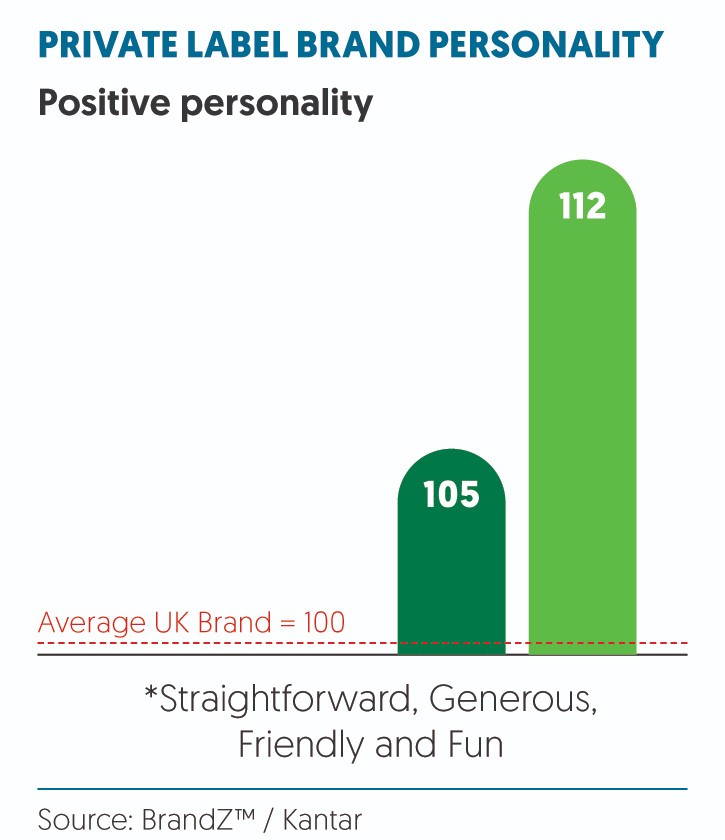

Private label brand personality

Several retailers have sought to humanize their PL offer with communications that add fun and playfulness to everyday scenarios using real people. ALDI’s “Like brands only cheaper” slogan and campaign plays on the similarity of product capabilities while seeking to differentiate on price.

What now for other brands?

The future looks bright for PL, with much improved advocacy levels suggesting a step change in perceived and actual quality. But what about the “real” grocery brands struggling to navigate this new landscape?

There’s little doubt that the best response will be to capitalize on PL’s lack of differentiation, and use the power of brand to make shoppers think twice about what they put in their baskets.

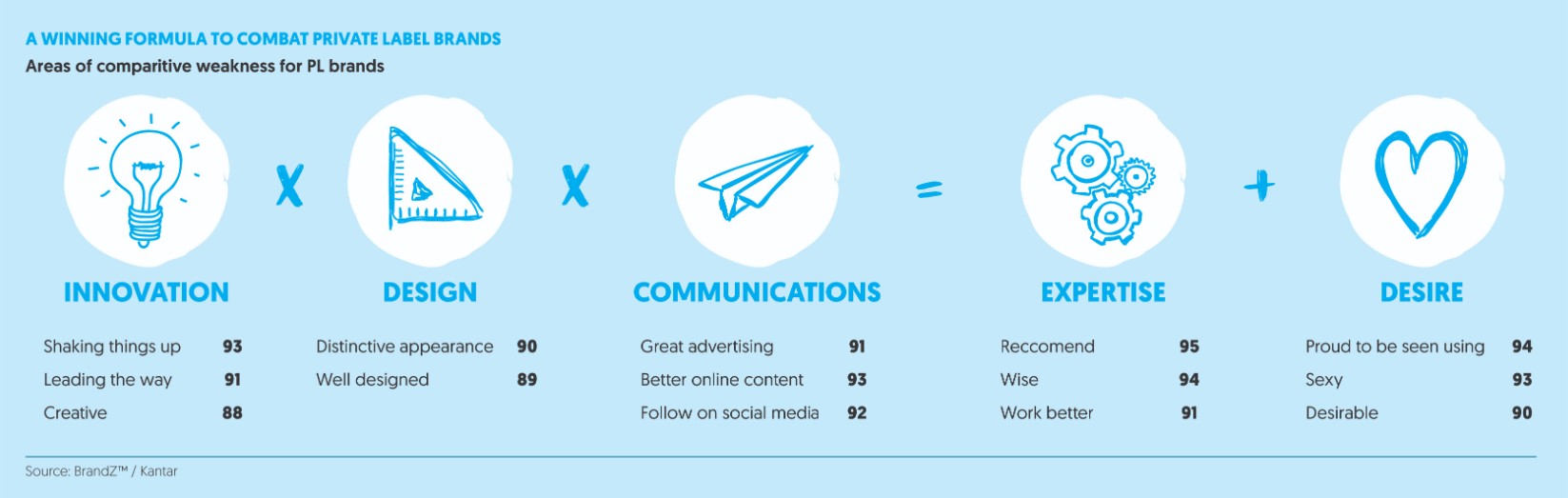

BrandZ™ data suggests that brands can use innovation, design and communication in combination to project a sense of expertise and create desire at levels that command a price premium to PL alternatives.

In essence, shoppers feel differently about PL brands, which have shaken off negative associations and are now seen as being straightforward, generous and approachable.

Indeed, the tactics deployed to combat PL by some of the leading UK grocery brands already draw on aspects of this formula – particularly investment in innovation to drive differentiation. Brands such as Lurpak and Persil are positioned as being “the best”, while Walkers have targeted a new consumption occasions with their “Max Strong” range, as have Maltesers with Maltesers Buttons. Halo Top ice cream and Elvive Dream Lengths hair products meet a previously unmet and emerging need.

These are the smart ones. What lies ahead for the others? Brands unwilling or unable to invest in underlining their point of difference will face further erosion of sales and will drift towards irrelevance. Our message to them is clear: differentiate or die.

*12 months to June 2019 vs 12 months to June 2015 – Kantar, Worldpanel FMCG

**12 months to Dec 2018 vs 12 months to Dec 2017 – Kantar, Worldpanel FMCG